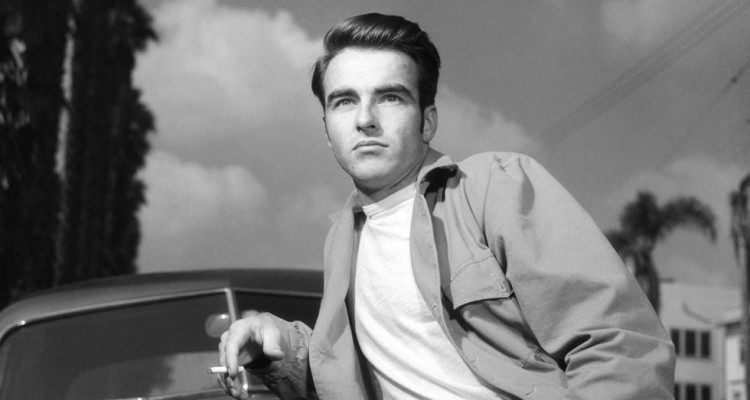

For over 30 years, scripts have floated around Hollywood promising to tell the story of Montgomery Clift, one of the most innovative and handsome actors in history. Tellingly, they’re always pitched under working titles like ‘Beautiful Loser’ and’ ‘Tragic Beauty’. Guided by the key biographies of Clift, they reliably parrot a narrative which paints the actor as a startlingly attractive and prodigiously gifted man who, according to one notably overheated tabloid TV show “became a drug-addicted alcoholic living in a self-imposed hell because he had a secret he couldn’t live with”.

That “secret” – that Clift was gay during an impossible era (the 1930s through the 60s) – led many interpreters to conclude that the actor must have led a life riddled with fear and shame. It hardly helped lend nuance to that reading that Clift was a well-known and long-time abuser of pain killers and alcohol, actions which likely sped his death from a heart attack at 45 in 1966. Yet, according to a new documentary, titled Making Montgomery Clift, the star’s substance abuse had nothing at all to do with his sexuality. In fact, the attitudes he and his family held towards his relationships with men were strikingly modern.

The movie, which plays at the LGBTQ movie festival NewFest in New York, refutes scores of oft-repeated assumptions about Clift’s life, from his motivations as an actor, to his relationship with his mother to the characterization of his later years. It also stresses Clift’s crucial role in changing the power balance between actors and studio chiefs in Hollywood, as well as the advancements he brought to film acting. More, it analyzes the new view of masculine beauty he helped introduce to the screen.

To help build their case, the film-makers had rare access to the actor’s archives, as well as to the family’s story, courtesy of a special connection: the doc was co-directed by the star’s nephew, Robert Clift, and his wife, Hillary Demmon. “For us, it seemed there was this big difference between what people thought about Monty in the public sphere and what people that knew him would say,” said Clift. “I wanted to figure out why there was such a difference.”

A deep trove of never-before-revealed evidence makes that disparity bracingly clear. For somewhat mysterious reasons, Robert Clift’s father Brooks taped endless conversations with his famous brother, as well as with their mother and other figures relevant to the story. (The director himself never met his famous uncle, having been born eight years after his death). In one tape made by his father in the 1960s, we hear the star’s mother tell him, with untroubled candor, that “Monty was a homosexual early. I think he was 12 or 13.”

“It’s obviously a non-issue for her,” co-director Demmon said. “That’s not what people would expect from a mother in that period.”

Then again, nothing about Clift’s life was expected. Born in 1920 in Omaha, Nebraska, Clift was raised like an aristocrat, with a private tutor and frequent trips to Europe. While he never excelled at school, his extraordinary abilities as an actor showed early. By 15, Clift made his Broadway debut in Cole Porter’s Jubilee. Over the next 10 years, he earned prominent roles in plays by Tennessee Williams and Thornton Wilder, opposite stars like Fredrick March and Tallulah Bankhead. Hollywood repeatedly came courting, but he put off offers for nearly a decade, even turning down roles in classic films like East of Eden and the co-lead in Sunset Boulevard.

Taped interviews with his brother reveal that the actor felt those roles weren’t quite right for him and he didn’t want to make the wrong first impression. He also didn’t want to sign a contract with a studio, then the only viable way into the business. “He didn’t want the studios to dictate the kinds of roles he would play,” his nephew said. “He wanted to be a free agent, and he did it successfully. The old Hollywood system was breaking apart and he was a major part of that.”

The first role Clift took, opposite John Wayne in Red River in 1948, offered a stark contrast in masculine presentations. Clift detested Wayne’s antiquated male constraints. He also detested the man. “Monty brought a different masculinity to the screen,” said Demmon. “Here was someone who was vulnerable and sensitive – and who actually listened to women.”

He wasn’t the only one who challenged such norms at the time. Contemporaries like James Dean and Marlon Brando also did. Like them, Clift was comfortable with the full contours, and consequences, of his beauty, playing “the object” in a way previously preserved for female stars. He also helped bring a more natural acting style to film. “That’s why his work doesn’t feel dated,” Demmon said.

He advanced a collaborative approach with his directors, working over scripts and making suggestions for edits. “He wasn’t solely an actor,” she said. “He had a holistic view.”

A fellow actor asserts that Clift was equally confident in his sexuality. Jack Larson, famous for playing Jimmy Olsen in the hit 1950s TV series Adventures of Superman, recalled how Clift gave him a full mouth kiss the first time they casually met. “He was not worried [about being gay],” Larson asserts in the film.

Another confidant said “his personal life didn’t bother him”

Observers also point out that Clift had sexual relationships with women. But, in general, his relationships with men had more to do with sex than with a deep emotional connection. A seeming exception was one in his final years with a man named Lorenzo who had been hired to help him. “They went to London to see Laurence Olivier together, ate together, sat in front of the fire together,” Clift said. “Lorenzo came into the picture when Monty was at his lowest. He got him going again. He still drank, but not as heavily. Lorenzo was one of the reasons.”

Clift asserts that the actor’s use of alcohol and prescription drugs stemmed, primarily, from a near-fatal car accident in 1956. He used them to numb his physical pain. The accident changed his appearance, and many biographers assumed Clift felt ruined by it and, so, drank more. But the documentary notes Clift made as many movies after the accident as before, and that those projects included some of his most acclaimed performances. Ex-lover Larson said in the film that Clift actually preferred his work after the accident to his performances before.

Many of the myths surrounding Clift sprang from two biographies: a salacious one by Robert Laguardia and another flawed work by Patricia Bosworth, titled A Life. The film-makers interviewed Bosworth extensively for the movie, but they contrast her words with old taped conversations she had with the actor’s brother. He pleaded with her to make changes to her book to correct the mischaracterizations. While she sounds apologetic, the changes were never made.

As to why Bosworth drew on the gay-self-hate narrative, and why that view took hold, the directors blame the homophobia of the time the book was written, in the 1970s. “The view then about queer people was that they would be inherently conflicted or tormented about their sexuality,” said Demmon. “If you have a story that tracks along that line, that will feel true to people. Which gives that narrative a lot of traction. Now we’re at a historical point in mainstream queer discourse where that story seems less viable.”

Though the film aims to update, and to fairly contextualize, the actor’s story, the directors stress that they don’t want to simply swap one image of Montgomery Clift for another. “We’re not trying to give a definitive version of who Monty was,” added Clift. “Part of honoring someone is being open to that person not being just one, reductive thing.”

Leave a Reply