If we were to take a television back in time – to the Middle Ages, say – and show off a Blu-Ray film (our time machine has a power supply), we can imagine that those medieval viewers would have no idea how we created such a stunning illusion.

Our audience would presumably want to try to look inside the television to see if we had a small crew of theater performers creating all these scenes – provided they hadn’t already burned us for the witchcraft of appearing out of nowhere.

Obviously, we have no confusion when we see an incredible scene on a television: Even when it can make us gasp or cry, we instantly know it’s fiction (or a technologically reconstructed representation of reality).

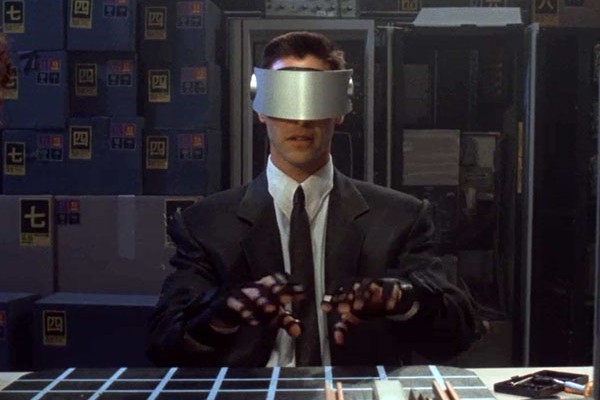

But due to advances in neuroscience that filmmakers are starting to incorporate into their work and because of technologies like virtual reality, “fictional entertainment” could soon be much more capable of convincing us that it’s actually real, that it simply must be. That’s both wonderful and a little terrifying.

Film scholars are starting to embrace neuroscience as a way of better understanding their audience. So far, that new school of study, known as neurocinematics, is mostly helping filmmakers understand what’s happening in a viewer’s brain as they watch a film. In the future, that knowledge could be used to make films that are even more captivating, immersive, and convincing.

And with VR, the power that creators have to convince their audience that something is real skyrockets.

It’s been said before, but it’s worth repeating: Until you’ve tried VR, you can’t imagine how convincing it is.

The three major VR headsets – the Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, and Playstation VR – are all out for sale now. They’re far from perfect and in many ways, VR game and experience creators are still trying to figure out how to make the best use of the systems. (Journalist Chris Suellentrop has written that even comparisons to the first iPhone, implying VR will get better soon, are early – he says that for now, it’s more like the first blocky carphones, that there’s a long way to go.) Yet even at this imperfect point, there’s still something magical that happens when your eyes tell your brain that what’s happening is real even though you know it isn’t.

When you try a horror experience in VR, immediately your heart starts pounding. Sure, it’s not real, but everything in your brain is screaming that it is. That’s the power new technology has to convince us.

“For the past 100 years, the way we have stimulated the visual system is that we have this 2D image in a fixed frame. But our visual perceptual system is tied into the movement of our heads and the movements of our eyes,” says Michael Grabowski, an associate professor of communication at Manhattan College and the editor of the textbook “Neuroscience and Media: New Understandings and Representations.”

When you look all around you and nothing disrupts the scene, it’s hard to really be sure that it’s an illusion. And that’s the magic of VR.

“When you put on VR goggles and your head movements are confirming with your visual systems what you’re seeing, your visual system is confirming it [too],” Grabowski says.

For now, filmmakers and game designers are still mastering the most effective techniques for storytelling with these new technologies. But as these experiences start to become more mainstream, it’s going to be fascinating to watch them slowly erode our grip on what’s real.

Leave a Reply